How to Make a 💡?

My favorite IDE feature is a light bulb — a little 💡 icon that appears next to a cursor which you can click on to apply a local refactoring. In the first part of this post, I’ll talk about why this little bulb is so dear to my heart, and in the second part I’ll go into some implementation tips and tricks. First part should be interesting for everyone, while the second part is targeting folks implementing their own IDEs / language serves.

The Mighty 💡

Post-IntelliJ IDEs, with their full access to syntax and semantics of the program, can provide almost an infinite amount of smart features. The biggest problem is not implementing the features, the biggest problem is teaching the users that a certain feature exists.

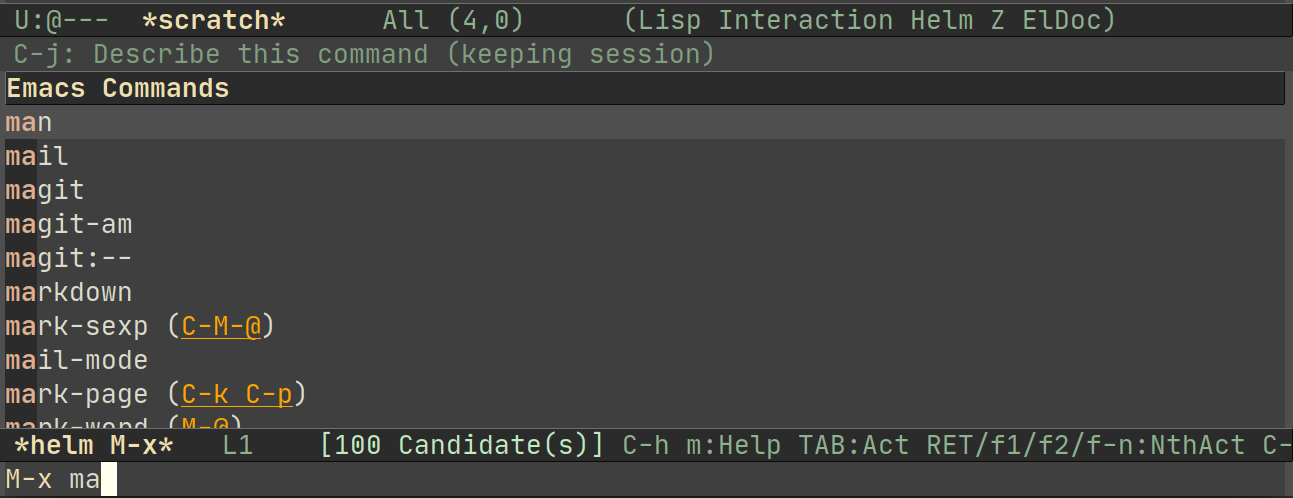

One possible UI here is a fuzzy-searchable command palette:

This helps if the user (a) knows that some command might exist, and (b) can guess its name. Which is to say: not that often.

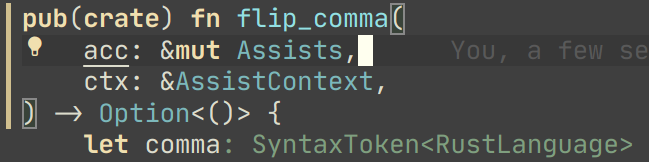

Contrast it with the light bulb UI:

First, by noticing a 💡 you see that some feature is available in this particular context:

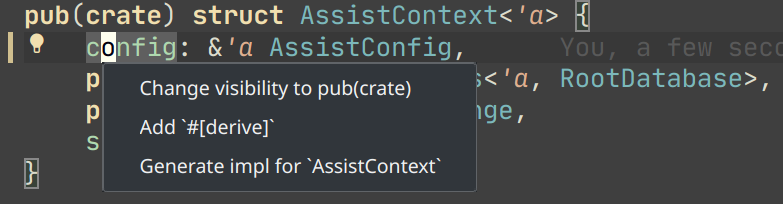

Then, by clicking the 💡 (ctrl+. in VS Code / Alt+Enter in IntelliJ) you can see a short list of actions applicable in the current context:

This is a rare case where UX is both:

-

Discoverable, which makes novices happy.

-

Efficient, to make expert users delighted as well.

I am somewhat surprised that older editors, like Emacs or Vim, still don’t have the 💡 concept built-in. I don’t know which editor/IDE pioneered the light bulb UX; if you know, please let me know the comments!

How to Implement a 💡?

If we squint hard enough, an IDE/LSP server works a bit like a web server. It accepts requests like “what is the definition of symbol on line 23?”, processes them according to the language semantics and responds back. Some requests also modify the data model itself ("here’s the new text of foo.rs file: '…'"). Generally, the state of the world might change between any two requests.

This is relevant for 💡 feature, as it usually needs two requests. The first request takes the current position of the cursor and returns the list of available assists. If the list is not empty, the 💡 icon is shown in the editor.

The second request is made when/if a user clicks a specific assist; this request calculates the corresponding diff.

Both request are initiated by user’s actions, and arbitrary events might happen between the two.

Hence, assists can’t assume that the state of the world is intact between list and apply actions.

This leads to the following interface for assists (lightly adapted

IntentionAction

from IntelliJ

)

1

2

3

4

5

interface IntentionAction {

val name: String

fun isAvailable(position: CursorPosition): Boolean

fun invoke(position: CursorPosition): Diff

}

That is, to implement a new assist, you provide a class implementing IntentionAction interface.

The IDE platform then uses isAvailable and getName to populate the 💡 menu, and calls invoke to apply the assist if the user asks for it.

This interface has exactly the right shape for the IDE platform, but is awkward to implement.

Almost always, the code at the start of isAvailable and invoke would be similar.

Here’s a bigger example from PyCharm:

isAvailable

and

invoke.

To reduce this duplication in Intellij Rust, I introduced a convenience base class RsElementBaseIntentionAction:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

class RsIntentionAction<Ctx>: IntentionAction {

fun getContext(position: CursorPosition): Ctx?

fun invoke(position: CursorPosition, ctx: Ctx): Diff

override fun isAvailable(position: CursorPosition) =

getContext(position) != null

override fun invoke(position: CursorPosition) =

invoke(position, getContext(position)!!)

}

The duplication is removed in a rather brute-force way — common code between isAvailable and invoke is reified into (assist-specific) Ctx data structure.

This gets the job done, but defining a Context type (which is just a bag of stuff) is tedious, as seen in, for example, InvertIfIntention.kt.

rust-analyzer uses what I feel is a slightly better pattern.

Recall our original analogy between an IDE and a web server.

If we stretch it even further, we may say that assists are similar to an HTML form.

The list operation is analogous to the GET part of working with forms, and apply looks like a POST.

In an HTTP server, the state of the world also changes between GET /my-form and POST /my-form, so an HTTP server also queries the database twice.

Django web framework has a nice pattern to implement this — function based views.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

def my_form(request):

ctx = fetch_stuff_from_postgres()

if request.method == 'POST':

# apply changes ...

else:

# render template ...

A single function handles both GET and POST.

Common part is handled once, differences are handled in two branches of the if, a runtime parameter selects the branch of if.

This pattern, translated from a Python web framework to a Rust IDE, looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

enum MaybeDiff {

Delayed,

Diff(Diff),

}

fn assist(position: CursorPosition, delay: bool)

-> Option<MaybeDiff>

{

let ctx = compute_common_context(position)?;

if delay {

return Some(MaybeDiff::Delayed);

}

let diff = compute_diff(position, ctx);

Some(MaybeDiff::Diff(diff))

}

The Context type got dissolved into a set of local variables.

Or, equivalently, Context is a reification of control flow — it is a set of local variables which are live before the if.

One might even want to implement this pattern with coroutines/generators/async, but there’s no real need to, as there’s only one fixed suspension point.

For a non-simplified example, take a look at invert_if.rs.